The climate benefits of smart growth may be far greater than we have thought

Those of us who focus on the ability of compact regional and neighborhood development patterns to reduce the need to drive so much – and that has certainly included me – are missing some important additional carbon savings from smart growth. Cumulatively, the additional reductions in greenhouse gas emissions that we have been neglecting may be just as significant as (or more significant than) those from reduced vehicle travel.

This comes from my friend Michael Mehaffy, who is managing director of the Sustasis Foundation in Portland, Oregon and a consultant, researcher and author on sustainable development and climate change. Mike spotted my blog post earlier this week on smart growth in the context of the Copenhagen climate summit and got in touch.

Mike acknowledges, as do many of us, that smart growth substantially reduces vehicle emissions by shortening trip distances and facilitating more efficient modes of travel. But, writing in “The Urban Dimensions of Climate Change” on Planetizen, he further argues from research that, because compact living also reduces the need to have as many vehicles, we can also reduce the environmental costs associated with their manufacture and related infrastructure. To get the complete savings “we must add the [foregone] emissions from the construction of the vehicles; the embodied energy of streets, bridges and other infrastructure; the operation and repair of this infrastructure; the maintenance and repair of the vehicles; the energy of refining fuel; and the energy of transporting it, together with the pipes, trucks and other infrastructure that is required to do so.”

The result increases the carbon savings by roughly 50 percent beyond that saved by reduced driving per se. But, wait, there’s more:

“Moreover, to the factors above we must add other significant contributions: the embodied energy and repair of other infrastructure, such as water, sewer and gas pipes, wires and so on; the energy required to pump or otherwise operate them; the significant 'transmission loss' of energy to more dispersed users; the very high efficiency possible in district-scale energy – particularly when it captures waste energy; and the ability to capture other efficiencies of co-location, such as waste heat from sewage."

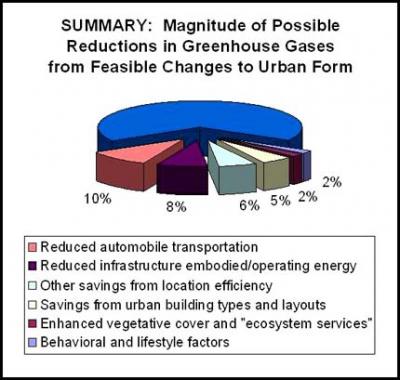

The list goes on to include reduced building emissions (we knew that part) from urban configurations and more indirect savings in the form of “ecosystem services” (less sprawl means more carbon-soaking green land) and, potentially, reduced demand for energy-consuming lifestyle choices that may be obviated by smarter neighborhoods and better public spaces (Mike concedes that this part is somewhat “thorny”). In combination, the additional savings could amount to double those from vehicle emissions alone, and the cumulative savings from all related categories could reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by as much as a third.

Emailing each other back and forth on Tuesday, Mike and I lamented that even members of our own environmental and urbanist communities can seem painfully slow to get it. I would argue that 20 years of almost exclusive attention to supposedly more straightforward remedies - more efficient vehicles, greener energy production technology, and big-picture standard-setting - though all worthwhile, have not exactly fixed the climate problem, either. Why not embrace additional strategies?

For those who are interested, I have a somewhat longer version of this post, with additional graphs and images, on my NRDC blog, where I post daily.

Comments

Write your comments in the box below and share on your Facebook!