Urban Designer Series: Robert Moses

In an attempt to dive a little deeper into what urban design is, and how it became the important profession that it is today, I have decided to start an “Urban Designer” series. Periodically, I will look at the most well-known urban design writers, scholars, and professionals throughout history and contemporary society. Some will have created the most influential of design movements, some will have created controversy, some will have answered the challenges created by those, some will answer the most pertinent issues of today. Most importantly with this series, I hope to paint a picture of the vast array of opinions and views of built environment professionals, but highlight the fact that the greatest focus on very similar principles.

There are many urban designers that this series could begin with like Kevin Lynch, Gordon Cullen, or Jane Jacobs : many are considered great in our history. However, I am beginning with the man whose urban planning philosophy was the precipice for the modern-day urban design profession. Without him, and the fore mentioned people who responded so passionately to his beliefs, I am not sure that I would have the career I do today.

His Philosophy and Work

Robert Moses began his career as an urban planner/highway engineer at the exact same time as the automobile was gaining favor and abundancy in America. Many would argue that it is no coincidence that his urban planning philosophy, in turn, was so car oriented. Moses came from a time when driving a car, was just not seen as utilitarian, it was seen as entertainment. As it became common place, planners shifted their focus from the experience of the pedestrian or the community, the experience of the driver. Robert Moses was not alone in his view, he just happened to be perpetuating it in the most high profile city in the world: New York City.

Moses was instrumental in the construction of the Triborough, Throgs Neck, Bronx-Whitestone, Henry Hudson, and the Verrazano Narrows bridges, as well as the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, Staten Island Expressway, the Cross-Bronx Crossway, the Belt Parkway, and Laurelton Parkway, just to name a few. Later in his career, the design of these roads shifted from a well-landscaped and beautified design, to the utilitarian highways we know today.

Moses was also a very political man, and had placed himself of a position of great influence. He was the Construction Manager in New York City after WWII and found himself in great favor with mayors and those who funded large construction projects. These bridges and highway systems he had masterminded made lots of money for the city, and in turn, he had power among other planning projects in the city. He also prohibited the creation of a city-wide Comprehensive Zoning Plan already underway, that would prohibited a majority of the visionary projects he had planned for New York City. With policy, funding, and politics in his corner there was little stopping him…New York was his.

No doubt influenced by other planners’ philosophy of the time, like Corbusier, Moses favored the eradication of “blight” and the construction of high-rise public housing projects. Historic neighborhoods and communities were bulldozed to make way for idealized and controlled housing plan across New York City. At the time these places were considered ghettos by many, and eradication was viewed as an improvement. It’s been reported that unlike other public housing authorities, at least those planned by Moses were high-quality construction. And many of them still stand today. Robert Moses built 28,000 apartments based on Le Corbusier’s “Radiant City” design scheme. With the separation of people, especially pedestrians, from cars and ground floor activity, an idealized design of the concentration of residents surrounded by green space was favored. If you look at the east side waterfront of Manhattan, the housing projects from 14th street to the Brooklyn Bridge are the result of Moses’ work.

His Legacy

Later, after duplicates of Moses’ work popped up all over the country, and led to worse blight than existed in the first place, his philosophy and work was questioned. Many cities today regret and constantly suffer from the social and economic impacts that have resulted from the highway segregation through urban fabric. Unpredicted by Moses, this is just one large negative impact that modernist urban planning had on communities. Moses would later witness that tower public housing led to the worse crime and ghetto conditions that cities had ever seen.

Some people have great respect for Robert Moses (many call him the Master Builder,) but if you ask most urban designers about him, they will quickly mention Jane Jacobs. I will write about Jane Jacobs in the next post in this series, but it was her realization of the negativity of Moses’ practices (revolutionary at the time) and her direct and explicit opposition to his projects and political gusto that set the foundation for the urban design profession today. Quite simply, if there were no Robert Moses, there might not be a Jane Jacobs as we know her, and there might not be urban design.

Robert Moses was one of the most politically active members of the modernist planning movement, and perhaps implemented more of the ideas than anyone on the ground. And for this reason, he is a famous character in the fruition of urban design. The sacrifice of the pedestrian in favor of the car, and the eradication and segregation of existing communities (no matter how blighted or poor) was a unique urban planning view. Since the car was a new invention, until then planning was based on the most traditional principles: people. This major shift in planning philosophy changed the way people lived everyday of their life because of large changes in their built environment. This new way of thinking was adopted long enough for there to be a large transformation in many of America’s largest cities, including New York City.

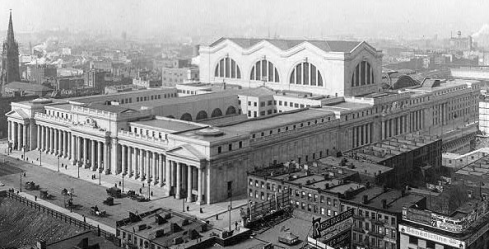

This questioning of Robert Moses’ beliefs and some of his personal actions led to the end of his era of planning. Many would argue it began with his encouragement to demolish the historic Penn Station (a New York landmark) in favor of a much less impressive development. Subsequently, he proposed that Greenwich Village and Soho be eradicated for the construction of a highway. This met so much opposition, it never occurred. Finally, he committed political suicide when he went up against governor, Nelson Rockefeller, who wanted to use toll money from one of Moses’ bridges to fund public transportation. No longer having the mayor’s trust and allegiance, Moses’ project ideas fell on deaf ears.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s is when urban design really became a vocation and later evolved into a profession. Before, that term truly wasn’t recognized. There was no need to return to traditional urban planning because it hadn’t been abandoned. Today, most urban designers (or at least everyone I’ve worked with) continue to work against the philosophy of Robert Moses. While most planners realize the destruction his work had on the city, its heritage, and communities, there is still a huge dependence on automobiles that still must be considered in policy making and development every day.

Robert Moses does have a positive legacy with his development of Long Island and the New York State Park system. Unfortunately that is often ignored due to the result of the 13 highways in New York City that have resulted in the eradication in the city’s character. There is no doubt, despite his ideas, that he was a huge influence in the creation of the urban design profession, which has been instrumental in sustainable design and development. And for that, we can be grateful for his career.

Erin Chantry is the author of At the Helm of the Public Realm. She is an Urban Designer in the Urban Design and Community Planning Service Team with Tindale-Oliver & Associates. Here is the original content.

Comments

Write your comments in the box below and share on your Facebook!