Urban Designer Series: Jane Jacobs, the Mother of Urban Design

In the first post of my Urban Designer Series I wrote about Robert Moses, the man whose urban planning philosophy was the precipice for the modern-day urban design profession. It was from his staunch modernist dogma that some of the greatest urban designers we know, such as Jane Jacobs who will be discussed in this post, responded so passionately to his beliefs. To any who have studied urban design, it’s been made clear that without the fundamental disagreement between the modernist planning beliefs centered on the automobile and urban renewal, and those that wished to return urban planning back to humanity and people, urban design would not be a profession today. We all still would be urban planners. The truth is that the automobile and planning principles accompanying it were instrumental in creating a demand for human-centered design.

Jane Jacobs was not a trained urban planner. She was a writer and an activist. As a concerned citizen she was able to see the negative and devastating impacts modern planning was having on communities and neighborhoods in New York City. She believed that a city was like an ecosystem that depended on a mix-of uses and planning based on community. This fundamental belief made her a tough critic of slum cleaning and high-rise housing, both practices that were becoming popular in New York in the 1950s. She was an instrumental catalyst in ground-up protest and activism, which undoubtedly saved many of the most loved parts of Manhattan today. However, it is her seven books, especially The Life and Death of Great American Cities, that propelled her an international scholar in planning; or as I call her, “The Mother of Urban Design.”

The Death and Life…

The Death and Life of Great American Cities was published in 1961 at the arguable height of the modernist urban renewal movement. This book is considered by many as the number one most influential work in American planning history.

Zoning laws that accompanied the urban renewal being practiced my modern planners separated uses (residential, commercial, industrial, institutional, etc.) from one another leaving places void of diversity and in many cases eradicating their identity. The Death and Life presents a lot in 458 pages, but perhaps most influentially advocates “four generators of diversity:” mixed uses, permeability, variety in the built environment, and high density that should determine the character of the city. She discusses how these effect the social and economic vitality of place.

The entirety of this work is based fundamentally on the fact that urban planners should discover the complexities and unique characteristics that determine how places work and enhance them, instead of write policy and design large projects that determine how a city should work. That argument: that places should be unique and reflect the identity of the people who live there instead of places answering to lofty academic principles of homogeneity is a fundamental core of urban design.

Throughout this book, Jacobs uses her own neighborhood, Greenwich Village, as a model for a healthy and active neighborhood. It is ironic that immediately following the book’s release Robert Moses was at the forefront of the project that would put a highway right through the middle of it, sacrificing Jacob’s own home. Here begins the battle of Jane Jacobs vs. Robert Moses.

Jane Jacobs vs. Robert Moses

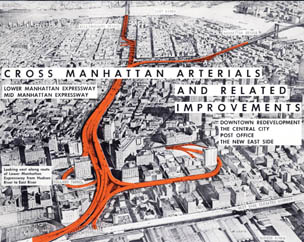

Robert Moses was focused on the automobile. His belief was that “cities are created by, and for traffic,” and in his love to move cars he had built tunnels, bridges, and highways to Manhattan, connecting Long Island to the city. It was his dream however to build three highways through Manhattan: the Lower Manhattan Expressway the first to be constructed. A small group of Greenwich Village residents were going to fight the Goliath of engineering and planning, and they chose their neighbor, Jane Jacobs to be David. Off the release of her book that was quickly climbing to fame, Jane Jacobs led a movement that rapidly grew, bringing different types of people together from throughout the city. The result was a strong and active coalition that appeared at every public hearing, wrote articles, protested in the streets, and counter-planned a healthy rehabilitation project for the neighborhood.

Moses’ only argument was that Jacobs and her coalition were simply too stupid to understand his plans and visions for the city. That this backlash was simply a case of nimbyism (“not in my back yard.”) And that when his projects were completed and the greater good was achieved that they would all be thanking him.

He did not have that chance. On December 11, 1962 the City Commission rejected the Lower Manhattan Expressway in favor of the argument that to Moses, expressways were more important than people and more than often his dreams turned out to be instead nightmares for the city. With this battle all over the media throughout the entire country it had become a political hot potato that every politician was forced to have an opinion on. Jane Jacobs not only ended the Lower Manhattan Expressway; it can be argued that she also ended Robert Moses’ career. His “super projects” lost favor politically. The notion that just because an idea was new, that it was good was soon dismissed by the power brokers in New York. Legend has it that Moses’ ego never recovered from not accomplishing his dreams in Manhattan.

Jacobs won another battled three years later on April 19, 1965 when the Landmark Preservation Commission was established. While it was two years too late to save Penn Station that fell victim to another Moses project, it has saved many buildings, districts, and neighborhoods that make New York City the place it is today.

Take a look at this great video summarizing the Jacobs vs. Moses battle.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=AUeuQT6t7kg

Her Legacy

Of course Jane Jacobs went on to write more works, solidifying herself as the “Mother of Urban Design,” including The Economy of Cities, which she herself believed should have been much more influential then the Death and Life. Because of her work (mostly) alone, the urban planning profession was forced to abandon it’s focus on what a city should be instead what a city was.Unfortunately it took a couple of more decades for profession to slowly come around to where the majority of professionals recognize that planning must have a bottom-up approach.

Today, every project must have an element of active public involvement and consultation. Meetings, hearings, charettes, and workshops are all funded through every project, with the belief that a plan is only as strong as the community that it serves. Buy-in from the public is perhaps one of the most sought after elements in urban planning. While this might seem as routine in the profession now, this would have been revolutionary to Jane and her coalition.

In addition, Jane Jacobs was able to look outside her front door and through nothing more than her humanity, define the four of the most important urban design principles that guide the development of many of the healthiest places in this country, and the world.

- Permeability – the belief that roads and pedestrian routes should be very-connected and intersect often to allow people an abundance of choice and efficiency in how they navigate an urban environment

- Mixed Uses – different uses (residential, commercial, institutional, etc.) in the same place strengthens the identity of a place and those that live there

- Density – the close proximity of the mixed uses to one another strengthens the economy of place and allows people to travel less distance for their daily needs

- Natural Surveillance – when the built environment is built at a human scale with buildings bordering public spaces, people watch them in their daily activities, which creates safe urban environments where people will feel welcome. The resulting active urban places foster a strong community.

Jane Jacobs also realized that these principles alone cannot create a healthy place, but actually they are interdependent on each other and act as a complex puzzle, than when put together correctly produce a unique identity each time. She broke down the building blocks of what urban planning should be, and these now form the toolbox of every urban designer – simply by watching the urban dance, or “ballet” that was on show just outside her front door. Jane Jacobs’ legacy has no doubt not only helped shaped cities across the globe, but made New York City arguably the best city in the world. Much to Robert Moses’ dismay I am sure, New York is one of the few places you can live in America without a car.

However, while the shift in urban planning has been shifting for more than four decades now, I often witness policy and projects that do not honor the Jane Jacobs’ legacy. She said she could see the whole city from her doorstep. Today, even in the biggest cities in the country that is not a truth. We still are alive and well in the zoning and separation of use planning culture that Jane fought so hard against. And there is no doubt that we are still entrenched in the world of the automobile. As streets are continually widened at the detriment of the pedestrian, and historic structures are demolished in favor of the bigger and better, we often times continue to build the world that Jane Jacobs fought so hard against.

Perhaps it’s because she stepped outside her gender role at a time where she was supposed to be doing nothing but cooking for her family and raising her children, or because she was short and slightly plump with an amazing fashion sense, or because she was a woman who never gave up on what she knew was right – she serves as a daily inspiration for me in my career. As an urban designer she is my hero and everyday I hope to spot the Robert Moses’ out there so I can make a fraction of the difference that she has in my industry and in my city.

Comments

Write your comments in the box below and share on your Facebook!